Researching the Men of Ashdown Forest who Fell in the First World War

Introduction

The Ashdown Forest Research Group — a small group of independent researchers whose work focuses on the history of Ashdown Forest — has undertaken a major project to write profiles of all the men who fell in the First World War and who are commemorated by the war memorials at Forest Row and Hartfield, two villages on the northern fringes of Ashdown Forest that traditionally have close links to the forest. The project was conceived as a way of marking the centenary of Britain's declaration of war against Germany on 4 August 1914.

In all, 113 individual case studies were written. They may be viewed online here at the Group's First World War website. Based largely on extensive Internet research, these illustrated studies contain detailed accounts of the recruitment and service of the men during the First World war, the actions they were engaged in and the circumstances of their deaths. They also explore the lives the men led before the war including their family backgrounds, local connections, education and occupations. The first case study was published in early 2014 and the last one was completed just two days before Armistice Day in November 2018. The studies since then have been subject to further minor revision and updating as new information and images have become available.

This illustrated essay aims to provide an overview of how the project was undertaken and to describe the key findings that have emerged. Click on the headings and sub-headings in the contents page below to jump to a particular section in the document.

CONTENTS

PROJECT OVERVIEW

- How the project started

- The war memorials

- How the list of men was compiled

- Sources of information

- The researchers

KEY FINDINGS

- The men on the war memorials weren't all local

- The men commemorated on Hartfield war memorial were more likely to be locally born than those on Forest Row war memorial

- The officers who are commemorated on the war memorials were less likely to have been locally born

- Some men only had tenuous links to the local area

- The men who fell were not particularly young

- Most men were killed in action or died from their wounds

- The number of fatalities fluctuated markedly as the war progressed

- A handful of battles accounted for the deaths of many men

- On occasion, several of the men died on the same day in the same battle

- Most of the men fought and died only a relatively short distance away from Sussex

- But some men died far away from home

- Several of the men died in the UK

- More than a quarter of the men who fell have no known graves

- Just over a quarter of the men served with the Royal Sussex Regiment

- But most of the men served in regiments other than the Royal Sussex Regiment

- Some men commemorated at Forest Row and Hartfield lost their lives at sea

- Some men commemorated at Forest Row and Hartfield lost their lives in aircraft

- Some families lost many men

- The relative impact of the men's deaths on the Forest Row community seems quite low

CONCLUDING REMARKS

APPENDICES

A1. MAPS

A2. TABLE

A3. LINK TO THE CASE STUDIES

A4. SOURCES AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A5. FURTHER READING

PROJECT OVERVIEW

How the Project Started

To mark the centenary of the First World War the Ashdown Forest Research Group has written case studies on all the men who died while on military service during the war and who are commemorated by the war memorials at Forest Row and Hartfield in Sussex. These are parishes which lie on the northern fringes of Ashdown Forest that traditionally have had strong links to the Forest.

The project began in late 2013 with the aim of completing all the case studies — 113 in total — by Armistice Day, Sunday 11 November 2018, the centenary of the end of the First World War.

To produce the case studies the Group researched the men's backgrounds, the lives they led before they went off to war, the details of their military service, the circumstances in which they died, their family and local connections, and the reasons why their names were recorded on the war memorials. The research has relied heavily upon sources of information available through the internet supplemented in some cases by information provided directly by relatives and others.

Each study as it was completed was added to a compilation document which was made available for viewing or downloading from the Group's page on the website of the Conservators of Ashdown Forest. The Group has since created a website dedicated to the project where each study can be viewed directly online. This is now the usual way in which the studies are accessed by members of the public.

The War Memorials

The starting point for the Group was analysis of the names inscribed on the war memorials at Forest Row and Hartfield. In addition the Group looked at the memorial plaque in Holy Trinity church at Coleman's Hatch, but the names recorded here proved with one exception to be a subset of those at Hartfield (see below). After the end of the First World War memorials to the fallen were erected up and down the country, funded by local subscription. Their openings reached a peak in 1920, which was the year the Forest Row and Hartfield memorials were unveiled.

Forest Row War Memorial

Situated on Lewes Road in the centre of the village, Forest Row war memorial was funded by public subscription. It was designed by the sculptor Ernest G. Gillick RA, whose other works included the Cenotaph in George Square, Glasgow. It takes the form of a sandstone tapering pillar about 18 feet in height with an inscription that reads: "In remembrance of the men of Forest Row who died for England in the Great Wars". The names of those who fell in the 1914-18 and 1939-45 wars are inscribed on the four sides of the pillar and on its plinth.

The unveiling of Forest Row war memorial in 1920

Forest Row war memorial was unveiled in 1920 by General the Honourable Sir Herbert Alexander Lawrence and his wife Isabella (granddaughter of the Earl of Harewood). The son of a Viceroy of India and a career soldier, Sir Herbert had risen to become General Haig's Chief of General Staff, British Armies France, 1918-19. He had lived at Ashdown Place, Forest Row, but by the time of the unveiling had moved to London. Both of his sons, Oliver Lawrence and Michael Lawrence, died in the Great War and are commemorated on the memorial.

Hartfield War Memorial

Hartfield war memorial, which stands on the High Street, was also unveiled in 1920. It is inscribed: "To the Glorious Dead of Hartfield". According to Historic England (both Forest Row and Hartfield war memorials are listed structures) it was erected to commemorate 40 local servicemen who died during the First World War. Built by Burslem Stonemasons of Tunbridge Wells, the memorial was unveiled on 10 October 1920 by John McAndrew and dedicated by the Rector of Hartfield. The names of the fallen from the Second World War were added at a later date. In 2013 a project was undertaken to improve the legibility of the inscriptions. In 2014 a further 15 names were added, comprising 11 First World War names and four Second World War names (including three civilians killed in an air-raid on East Grinstead in July 1943).

The Memorial Plaque, Holy Trinity Church, Coleman's Hatch

The memorial plaque inside Holy Trinity Church, Coleman's Hatch, built in 1913, was produced by R. Thompson of Kilburn. All those men named on it who fell in the First World War are also commemorated on Hartfield war memorial. However, in addition, within the church there is a small plaque, installed in 1928, dedicated to Lt. George Baylay, who died in the War and who is not named on the war memorials at Hartfield or Forest Row. Lt. Baylay was added to the list of case studies.

In a couple of cases, the same men are recorded on both the Forest Row and Hartfield war memorials. This is not surprising given the proximity of the villages to each other.

In many cases the names of some of the men commemorated on these war memorials also appear on other memorials elsewhere in Britain (e.g. school, college or university rolls of honour, regimental rolls of honour, etc.) and overseas (e.g. listed on battlefield memorials). The case studies identify these memorials where known.

Book of Remembrance, Holy Trinity Church, Forest Row

.jpg)

Entry in Forest Row's Book of Remembrance

for Albert Mitchell

Associated with the war memorials are books of remembrance. The Group referred in particular to one kept at Holy Trinity Church, Forest Row. This contains information about the men on Forest Row war memorial that was supplied after the war by, usually, close relatives such as spouses and parents, and was drawn upon in writing the case studies.

Compilation of the List of Men to be Studied

The first task of the Group was to create a list of men named on the war memorials at Forest Row and Hartfield who had fallen in the First World War. The memorial in Forest Row names 65 men, while the memorial in Hartfield names 51 plus there is, in addition, one man, George Baylay, who is commemorated by his own dedicated plaque inside Holy Trinity church, Coleman's Hatch. This gives a total of 117 names. However, two men (George Fisher and Edward Luxford) appear on both war memorials at Forest Row and Hartfield, which reduces the number of men to be researched to 115. Of these 115, the Group could find nothing about two men (Pte. Frederick G Story and L/Cpl G A West) beyond their names and ranks (indeed, we cannot even be certain that they were casualties of the First World War). Consequently the Group produced case studies on 113 men, which were all published on the Group's First World War website. It is these 113 men who are the subject of analysis in this present essay.

Finally, it should be noted that one man named on Hartfield war memorial, Charlie Wheatley, died in a drowning accident at Portsmouth in 1921, well after the war had ended but has been included in the published case studies nonetheless.

Sources of Information Used by the Group

In carrying out its research, the Group has relied extensively information available online, much of which has become available quite recently. When researching the men's lives before the war, a key source was the decennial census of population, which was available online up to the 1911 census. The census enumerations made it possible to identify the men and the members of their families, their ages and occupations, and their changes of location from decade to decade.

As far as war service was concerned, extensive use was made of a wide variety of official war records that are available online, including the website of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC), which also provided very useful information about cemeteries and memorials, and specific information about the men such as their grave registration report forms. For information about the men before, during and after the war online press reports available through the British Newspaper Archive were valuable. Many other sources were also drawn on including school and college archives.

The case studies acknowledge particular sources wherever possible. The online case study website includes a Sources and Acknowledgements page for the project.

In writing the case studies members of the Group have received helpful information from relatives of the men who are commemorated, for which we are most grateful. We would welcome any further information, and also photographs, which would help us to improve the case studies. We would also welcome any corrections to the errors that will inevitably have crept into our work.

The Researchers

The case studies were researched and written by Pam Griffiths, Vivien Hill, Carol O'Driscoll and Kevin Tillett. The project co-ordinator, editor and webmaster is Martin Berry.

KEY FINDINGS

Our research highlighted many aspects of the Great War — and of the war memorials themselves — that were not obvious to us when we began our project. It also revealed something about the environments which the men came from, their different social backgrounds and ways of life before the war. Here are some key points that emerged from the project.

1. The men on the war memorials weren't all local

When the Group began its work it expected that the men commemorated on the war memorials would mainly be locals with close connections to Ashdown Forest. As Tiller wrote in her excellent overview of war memorial building after the war:

"...the central task of war memorial committees was to ensure that all those killed who could be counted as local to the relevant area were included in the primary local memorial." (Tiller, 27)

However, in the case of our war memorials the qualification for being regarded as 'local' was broadly defined, so that some of the men listed only had brief relationships or tenuous connections with these villages, for example because their parents had moved into the area and wanted them to be commemorated here.

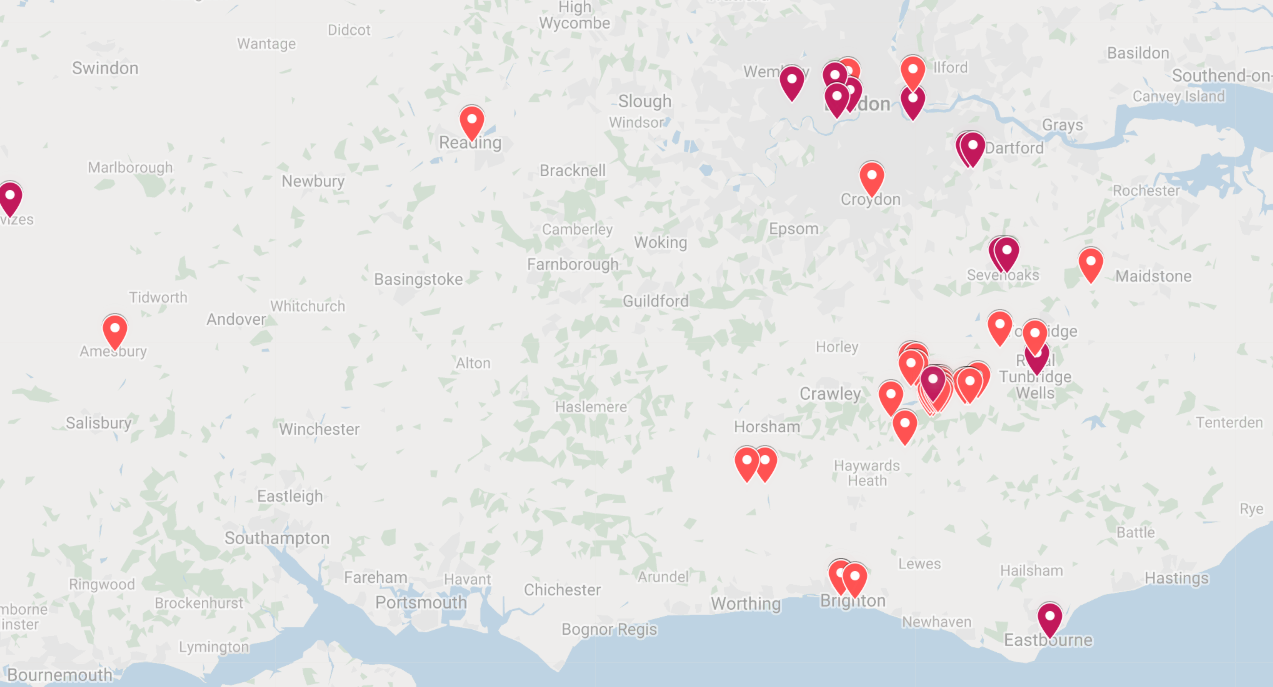

Birthplaces of the men commemorated

on Forest Row and Hartfield war memorials

If we consider the place of birth as being the primary consideration for being regarded as 'local', only about half (49%) of the men on the two war memorials were born in Forest Row or Hartfield (see chart above).

If we cast the geographical net wider to the county level, 68% were born in Sussex. This still leaves almost a third who were born outside the county.

That said, a significant number of the men were born in parishes in Kent that bordered Forest Row and Hartfield, so it's not surprising that 15% of the men were recorded as born in that county.

There are of course many examples of men commemorated on the war memorials whose families had long been resident in the area. Private Walter Martin, who died in the Battle of the Somme aged 18, is the youngest man commemorated on Forest Row's war memorial. The son of a brewer's drayman, he was born in the centre of the village. It was his mother who supplied his details for the village's book of remembrance.

Two families with widespread and long-standing connections to the area who tragically are represented several times on the two war memorials, the Maskells and the Wheatleys and Weedings, have been researched in detail by the Group and are described elsewhere in this document.

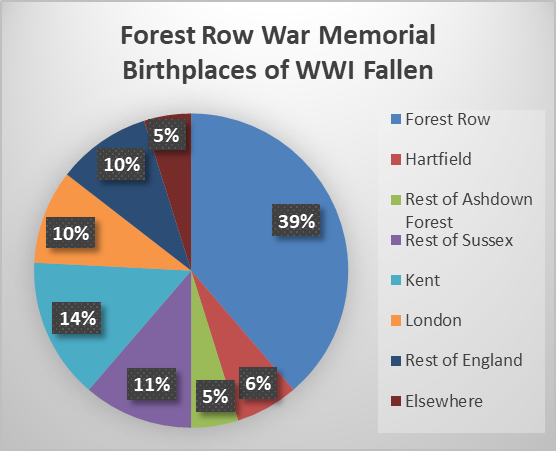

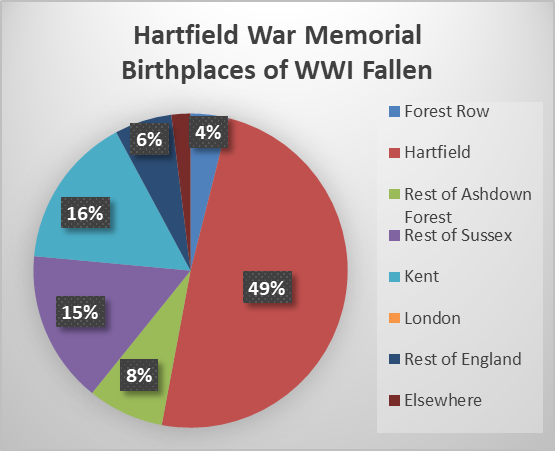

2. The men commemorated on Hartfield war memorial were more likely to be locally born than those on Forest Row war memorial

There is a considerable difference between the two villages in the proportion of locally born men listed on their war memorials, as the pie-charts below illustrate. In the case of Forest Row two-fifths (39%) of the men were born in Forest Row parish whereas in the case of Hartfield almost half (49%) were born in Hartfield parish.

The contrast remains if we look beyond the two parishes and consider the proportion of men who were born in the county of Sussex: 76% of those named on Hartfield war memorial were Sussex born compared with 61% in the case of Forest Row war memorial.

Finally, looking at this from a different angle — the proportion of men who were born in neither Sussex nor Kent — we find that a mere 8% of the men commemorated at Hartfield were born outside Sussex or Kent compared with almost a quarter (24%) of the men commemorated at Forest Row.

These contrasts reflect differences in the populations of the two parishes and their relative openness. Forest Row had developed a more diverse population in the latter half of the 19th century as improved communications and recreational attractions such as the Royal Ashdown golf club (opened in 1888) brought in people — especially the well-to-do and newly retired — from outside the area to settle. Hartfield by contrast remained rather insular.

To underline this point, it is significant that six of the men named on the Forest Row memorial had been born in London, and of these four were army officers whose well-to-do parents had moved to Forest Row to live in large country houses. By contrast, none of the men listed on Hartfield war memorial had been born in London, while there are only two officers commemorated on Hartfield's war memorial, both of them born in the parish.

Mapping the men's birthplaces

Places of birth of the men commemorated on Forest Row war memorial (left) and Hartfield war memorial (right) (south-east England only — click to enlarge)

The above map shows the birthplaces of the men on Forest Row war memorial as red markers (officers in maroon) and those on the Hartfield war memorial as green markers (officers dark green). Only birthplaces in south-east England are shown. The map illustrates that the birthplaces of the men listed on the Forest Row memorial are more geographically dispersed than those at Hartfield.

Interactive map

The above maps are snapshots taken from the interactive Google map below, which may be accessed by clicking on the image (map opens in a new window). The interactive map shows the birthplaces of all 113 men in the cohort. It is zoomable. Clicking on a marker reveals the man's name and a hyperlink to his case study. As above, the red markers refer to men commemorated on the Forest Row war memorial (maroon markers = officers) and the green markers to men commemorated on Hartfield war memorial (dark green markers = officers).

Interactive Google map showing the places of birth

of the men commemorated on the war memorials (click to view)

3. The officers who are commemorated on the war memorials were less likely to have been locally born

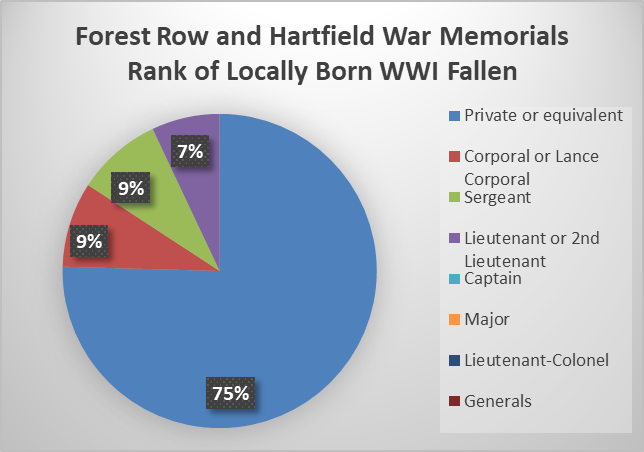

The above pie charts show the military ranks of the men commemorated on Forest Row and Hartfield war memorials at the time of their deaths. They indicate that locally-born men (left-hand chart) were much less likely to be officers than those who were not born locally (right-hand chart). Only four of the 57 men (7%) on the war memorials who had been born locally were officers, Frederick Polehampton, William Melville, Eric Waters, and Cyril Robinson, and they were all lieutenants, rather than captains or other higher ranked officers. Fully three-quarters (75%) of the locally-born men were serving in the lowest military rank as privates or equivalent.

By contrast, a large proportion of those who had not been born locally were officers (right-hand chart) — 19 out of 56 (34%) — and they occupied all the army ranks below general: second lieutenant, lieutenant, captain, major and lieutenant colonel. Only 57% were serving as privates or equivalent.

(Purely as an aside, it is interesting to note that of the 23 officers commemorated on the war memorials (20% of the total), most (60%) had attended public schools. Seven had been pupils at Eton alone, and another seven had been at other well-known schools such as Harrow, Rugby, and Haileybury.)

4. Some men only had tenuous links to the local area

A number of men commemorated on both war memorials had only tenuous connections to Forest Row or Hartfield, particularly those who were officers. A handful had probably never visited the area. The reason they were named on the war memorial might have been that their parents had moved to the district, perhaps after retirement or after acquiring a second home there, and it was they who ensured that the names of their son (or sons) were represented on the war memorials that were erected locally after the war. For example, Captain Wilfred Brownlow probably never saw Forest Row but he is commemorated on the war memorial because his parents settled there after his father retired from the Army.

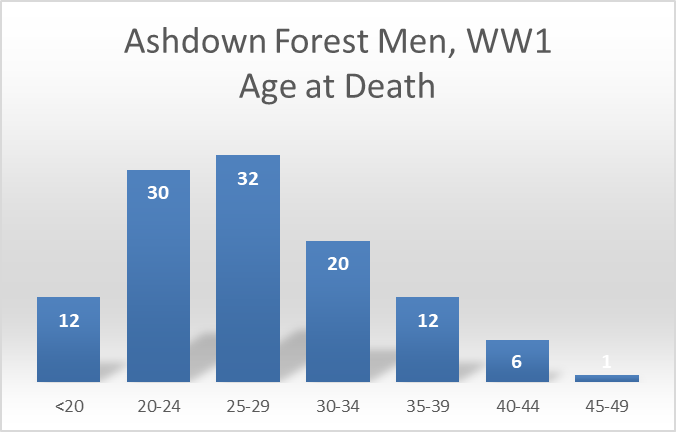

5. The men who fell were not particularly young

Age at death of the men commemorated on Forest Row

and Hartfield war memorials (WWI casualties only)

During the First World War the minimum age for military service was 18, and 19 if serving overseas. The maximum age was 38. The men in our cohort were not particularly young, as the above graph illustrates: their average age was 27, and more than a third (39%) were aged 30 and over. Indeed, seven were in their forties, above the official maximum age.

Only twelve of the 113 men we studied were under 20. The youngest men were two privates, Philip Thomsett and Walter Martin, who were aged 18 when they died in the Battle of the Somme in 1916. Walter Martin's body was never recovered, and he is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial. Philip Thomsett was gravely wounded and repatriated to England, where he died in the First London General Hospital, Camberwell. He is buried in Forest Row cemetery.

The oldest man, who died at the aged of 46, is also one of the most unusual. Edmund Fisher was born in Kensington in 1872, the sixth of eleven children. He came from an elite family. His siblings included H.A.L. Fisher, historian and Minister of Education; Admiral Sir William Wordsworth Fisher; Florence Henrietta, playwright and wife of Sir Francis Darwin (son of Charles Darwin); and Adeline Vaughan Williams, wife of the composer Ralph Vaughan Williams. Educated at Haileybury public school, he became an architect. At the outbreak of war he was too old for active service but, after training with the Royal Field Artillery, he was accepted for active service from June 1917 and fought on the Western Front as a 2nd Lieutenant. Unfortunately, he was struck down with appendicitis in January 1918 and died of peritonitis in March. Buried at Brockenhurst, he is commemorated on Forest Row war memorial because he was married to Janie Freshfield, daughter of Douglas Freshfield, a lawyer and celebrated mountaineer, who resided at Wych Cross Place in Ashdown Forest.

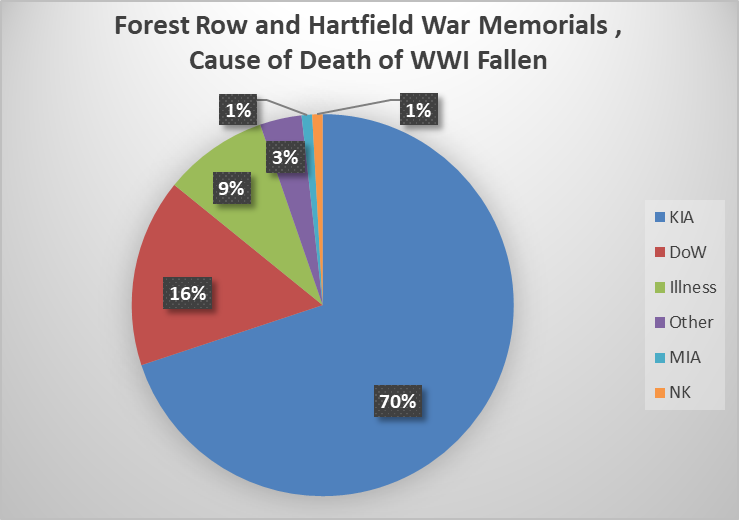

6. Most men were killed in action or died from their wounds

Cause of death of the men commemorated on Forest Row

and Hartfield war memorials (WWI casualties only)

Unsurprisingly, most of the men in our cohort were killed in action (80) or died of wounds (18). But the next most important cause of death was illness (10). More specifically the causes were bronchio-pneumonia (3), malarial fever (2), and heart failure, shell shock, appendicitis, encephalitis and influenza (1 each). It is striking that, despite the devastating epidemic of Spanish Flu towards the end of the war, possibly originating in late 1916 at the major hospital camp at Étaples in the Pas de Calais, only one man in the entire cohort, Private Ernest Cannon, died from influenza, a week before the Armistice.

Of the four remaining deaths three involved aviation or naval accidents. Two men, Keith Lucas and Nigel Whitfield, both captains in the Royal Flying Corps, died in England in air accidents. Ordinary seaman Charlie Wheatley, died in 1921 in a drowning accident that had no direct connection with the war. The final death was sadly a suicide. Lt Col William Sykes, the highest ranked officer in the whole cohort, shot himself at his barracks at Tidworth, Wiltshire. His suicide was attributed to "overwork".

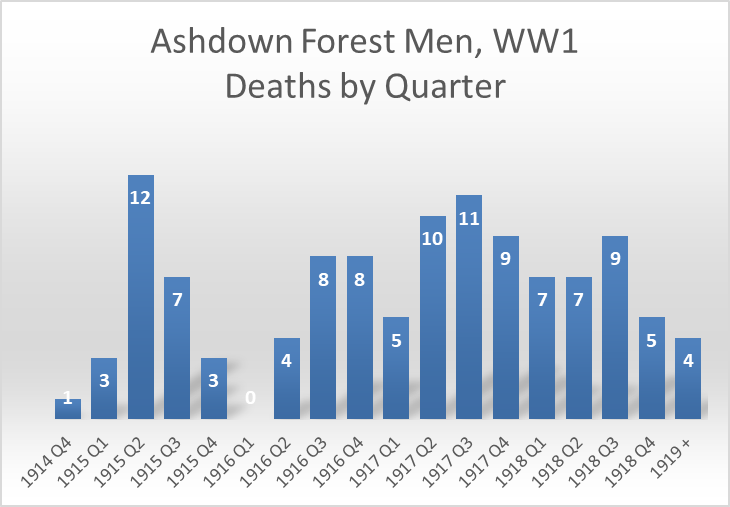

7. The number of fatalities fluctuated markedly as the war progressed

Deaths by quarter of the men commemorated on Forest Row

and Hartfield war memorials (WWI casualties only)

The number of fatalities fluctuated markedly as the war progressed. As the above graph shows, in the first part of the war there was a distinct peak in the second quarter of 1915, followed by a decline and then a complete absence of fatalities in the first quarter of 1916. However, the third quarter of 1916 saw a sharp rise. The Somme offensive began on 1 July 1916 and many of the men in our cohort lost their lives in these and the ensuing battles on the Western Front. Casualties later climbed still further in the second and third quarters of 1917. A final peak occurred in the third quarter of 1918, the culmination of the German spring offensive.

Fatalities however did not end with the war. Five men died after the Armistice from illnesses contracted during the war.

8. A handful of battles accounted for the deaths of many men

Four battles on the Western Front accounted for the deaths of a large number of the men in our cohort. The Battle of Loos (25 September-15 October 1915) accounted for four, the Battle of the Somme (1 July to 18 November 1916) twelve, and the Battle of Arras (9 April-16 June 1917) and the Third Battle of Ypres (31 July-10 November 1917) seven each. In these four battles 29 men died — a quarter of the 113 men we studied.

9. On occasion, several of the men died on the same day in the same battles

It is striking that there were ten occasions when two or more men fell on the same day in the same battle, accounting for 24 of the 113 men in the cohort.

For example, four men who are commemorated on Hartfield war memorial all died on Sunday, 9 May 1915 on the Western Front, fighting in the same small area of Flanders around Richebourg l'Avoué in the Battle of Aubers Ridge. Privates Frederick Edwards, Thomas Honeysett and Doctor Wheatley were serving with the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Sussex Regiment while Lieutenant William Melville was attached to the King's Royal Rifle Corps. None of them have a known grave, but are all commemorated on Le Touret war memorial.

Two years later three men — Private Albert Gladman, Trooper George Weeding and Lance Corporal George Wheatley — were killed in action on 3 May 1917 on the Western Front in the Battle of Arras. Private Gladman of the Royal Fusiliers was buried in Faubourg d'Amiens cemetery, Trooper Weeding of the Household Battalion was buried in Roeux British Cemetery, but the remains of Lance Corporal Wheatley (a distant relative of Trooper Weeding), of the Royal West Kent Regiment, were not recovered; he is commemorated on the Arras Memorial.

Later that year, in Palestine, where the British forces were defending Gaza from the onslaught of the forces of the Ottoman Empire, three men — Captain Hanbury Kekewich, Private George Baker and Ernest Harding — died on 6 November 1917 during the Third Battle of Gaza. All were buried in Beersheba war cemetery, alongside Hanbury Kekewich's younger brother, George, who had died of wounds nine days earlier. Captain Kekewich and Private Harding were both serving with the 16th Battalion (Sussex Yeomanry) of the Royal Sussex Regiment, while Private Baker was fighting with the East Kent Yeomanry (The Buffs).

In addition, there were five occasions when two or men died on the same day in different locations. This accounts for another 10. So, altogether 34 out of 113 men were killed on the same day. This represents 30% of the cohort.

10. Most of the men fought and died only a relatively short distance away from Sussex

.jpg)

Parliamentary Recruiting Committee poster, 1915

The war in France and Belgium was close to home for the men of Ashdown Forest and their families. The devastating fighting on the Western Front took place only a relatively short distance away across the English Channel (for example, Ypres, shown on the poster by the soldier's left foot, was only 125 miles away from Ashdown). Indeed the constant rumble of the heavy bombardments could be heard from the Forest. As the headmaster of Fletching School, Robert Saunders, noted in a letter to his son in Canada:

"The great blot on everything is the thud and throb of the guns night and day in France, and yesterday I could even hear them indoors."

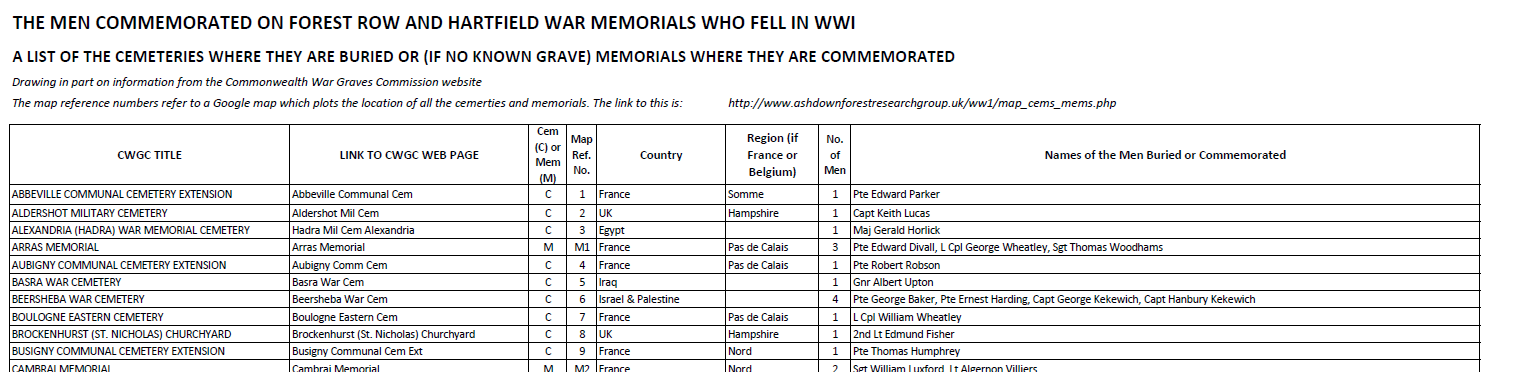

Many Ashdown men fought and fell on the northern part of the Western Front that lay in north-east France and west Flanders, and are buried or commemorated there. The map below shows the cemeteries (blue discs) where they are buried and the memorials (red discs) where those with no known grave are commemorated.

Cemeteries and Memorials - Western Europe

(click image to go to a zoomable, interactive map)

A list of all the cemeteries and memorials plotted on the Google map above and of the men who are buried or commemorated in them may be viewed by clicking here.

On the Western Front 53 men are buried in 44 cemeteries, and another 29 are commemorated at 9 battlefield memorials, most notably Thiepval in the Somme region (6 men) and Loos (5 men) and Le Touret (4 men) in the Pas de Calais.

The cemeteries and memorials associated with the Western Front battles in which the men fought, such as Béthune, Festubert, Arras and Ypres, are clustered in northern France and western Belgium. Many of the battlefields lie only about 115-130 miles away from Forest Row and Hartfield as the crow flies. Some are little more than 60 miles from the Channel ports of Calais and Boulogne.

A number of the overseas cemeteries in which the Ashdown men are buried are even closer. Some of the men who were wounded were taken to hospitals on the French coast, and those who died in them were buried in neighbouring military cemeteries. One of the most important military hospitals was at Étaples, near Le Touquet. Three of our men were taken there and are now buried in the adjacent Étaples military cemetery. Another man died in a hospital at Boulogne where, on a clear day, the coastline of Sussex and Kent would have been visible on the horizon.

11. But some men died far away from home

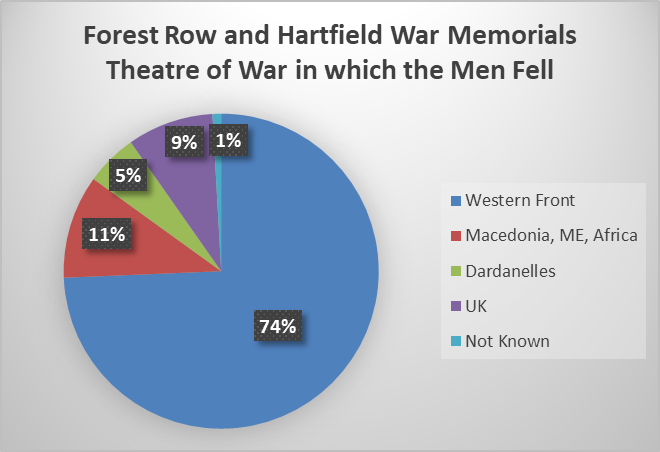

Theatre of war in which the men commemorated on Forest Row

and Hartfield war memorials fell (WWI casualties only)

When we think of the men who fell in the Great War we naturally think of the Western Front in France and Belgium. Indeed 84 men died there, almost three-quarters of our cohort (74%) — see chart above.

But 18 men, about one-sixth of the total (16%), died while serving much further afield. The map below shows the cemeteries where they were buried (blue discs) and the memorials where they are commemorated (red discs).

Cemeteries and Memorials - Eastern Mediterranean, Middle East and Africa

(click image to go to a zoomable, interactive map)

Six men fell during the disastrous Gallipoli/Dardnanelles campaign of 1915 in Ottoman Turkey. They were Benjamin Mellor, Arthur Kennard, James Simmons, Alfred Sands, John Shelley and Ernest Vaughan. None of them have known graves (three of them were lost at sea). They are all commemorated on the Cape Helles memorial, the great stone obelisk on the tip of the Gallipoli peninsula that is so visible today to ships passing through the Dardanelles strait.

Two men died in Salonika: one, Albert Richardson, was killed in action on the Salonika front, the other, Frederick Southey, a driver in the Royal Army Service Corps, died in hospital from illness, possibly malaria.

In 1917 six men died in Gaza, Palestine, including three (George Baker, Ernest Harding and Hanbury Kekewich) on the same day, 6 November 1917, in the Third Battle of Gaza, while, the following year, in Egypt, Gerald Horlick, a scion of the malted drink family, was to die of malaria contracted while on active service.

Two men, Albert Upton and Jack Sippetts, died in Mesopotamia (in present-day Iraq and Iran) between Basra and Baghdad, where the British were seeking to defend strategic oil wells.

Finally, Harold Grayer died in east Africa, in what is now Mozambique, where the British were fighting with their allies on the "Forgotten Front" to drive the Germans out of their colony of German East Africa. His cemetery is located in Pemba, today a tourist resort overlooking the Indian ocean.

How strange and alien the men of Ashdown must have found it serving in these faraway places.

12. Several of the men died in the UK

As the pie chart in the preceding section indicates, 9% of the men died in the UK. Some were lost because their ships were torpedoed in English coastal waters, some in air accidents, others died of illness and one committed suicide.

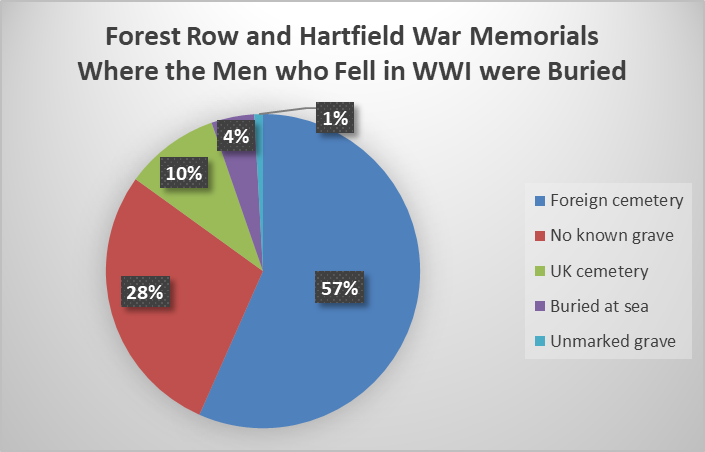

13. More than a quarter of the men who fell have no known graves

Where the men commemorated on Forest Row

and Hartfield war memorials were buried

More than a quarter (28%) of the men commemorated on Forest Row and Hartfield war memorials have no known grave.* The Western Front, disproportionately, accounts for 88% of them.

For those men with known graves, more than half in the cohort (57%) were buried in foreign cemeteries, and the Western Front accounts for 83% of them. Until 1915 many bodies were brought home but the scale of the casualties meant this was deemed impossible and unsanitary. The Imperial War Graves Commission, founded in 1917, resolved not to repatriate bodies and decided to bury them beneath matching memorials with plain gravestones to avoid distinctions based on class or rank (a policy which aroused some controversy; see for example Shaping Our Sorrow).

Five men were lost or buried at sea. Two were serving in the Royal Navy close to the coast of England, three were soldiers lost when their ships sank during the Gallipoli campaign.

Closer to home, six men are buried in the cemetery of Holy Trinity Church, Forest Row, two are buried at Holy Trinity, Coleman's Hatch, and one is buried at St.Mary's, Hartfield.

*For comparison, official War Office statistics indicate that about half the men who fell during the war were buried as known soldiers, with the rest either buried but unidentifiable or lost. (Source: The Long Long Trail)

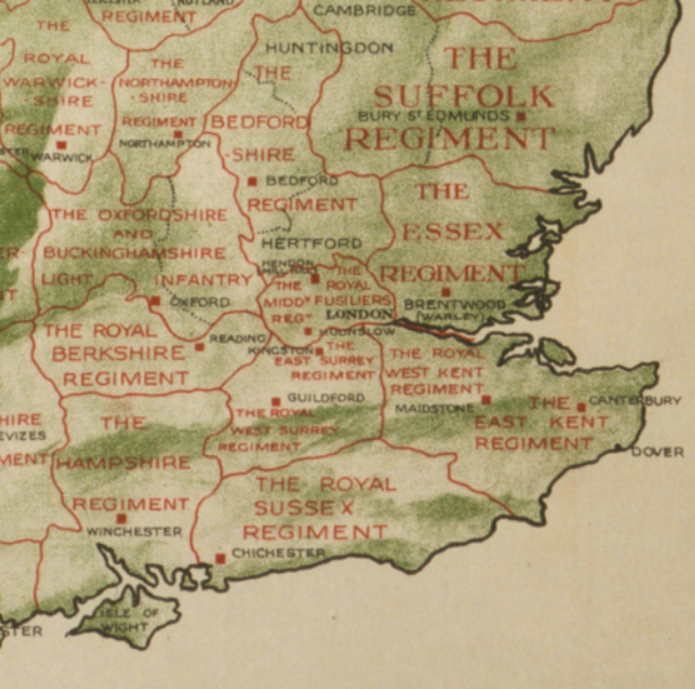

14. Just over a quarter of the men served with the Royal Sussex Regiment

Regular Army recruiting grounds, south-east England (1915 poster)

This poster shows in map form the recruiting grounds of the regular army in 1915. Traditionally the men from Forest Row and Hartfield would have enlisted with their county regiment, the Royal Sussex Regiment. In fact, just over a quarter of the cohort — 32 men, 28% of the total — were serving with the Royal Sussex Regiment at the time of their death.

The Southdown Battalions

Soon after the war began it was realised (particularly by Lord Kitchener) that there was an urgent need to recruit large numbers of men to serve in the armed forces. A drive ensued to recruit men into Kitchener's New Armies and into existing territorial regiments including the new 'Pals' battalions which successfully recruited groups of men from workplaces, villages, educational institutions, and so on. The Royal Sussex Regiment's 11th, 12th and 13th battalions — 'The Southdowns' — were 'pals' battalions raised and equipped with Kitchener's agreement by Claude William Henry Lowther, Unionist MP for North Cumberland, who had acquired Herstmonceux castle in 1910, and they subsequently became known as "Lowther's Lambs". The battalions were formed at Bexhill on 20 November 1914, where some 1,100 men enlisted in 56 hours. Lowther held the temporary rank of Lieutenant-Colonel but he did not lead the men to France himself, and withdrew to Herstmonceux. The three battalions were later to suffer heavy casualties at Ferme du Bois near Richebourg l'Avoué on 30 June 1916 in a diversionary attack twenty-four hours before the Somme offensive was launched. The disaster, in which 366 men died and over 1,000 were wounded or taken prisoner, became known as "The Day Sussex Died". Four of the men commemorated on the Forest Row and Hartfield war memorials were serving with the Southdown battalions, but none of them fell on that day.

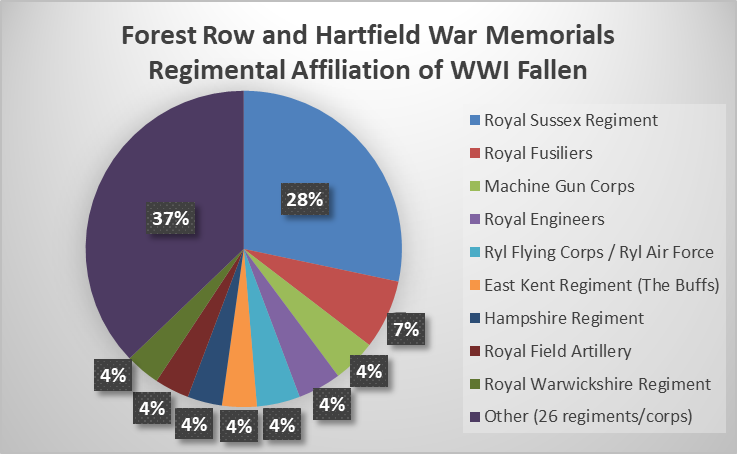

15. But most of the men served in regiments other than the Royal Sussex Regiment

Regimental affiliations of the men commemorated on Forest Row

and Hartfield war memorials at the time of their death

Despite it being the 'home' regiment for men of Sussex, the majority of the men in the cohort served in regiments other than the Royal Sussex Regiment. Only just over a quarter (28%) of them were serving with the latter at the time of their death. The pie chart shows the other main regimental affiliations. The proportion of men who were serving with the RSR may seem low, especially given the efforts to recruit volunteers into the regiment in the early years of the war. Partly this is to do with where Forest Row and Hartfield parishes are situated, on the north side of Ashdown Forest close to Kent and Surrey and not far from London. Some men had strong personal, family and work-related ties especially to Kent and London, so it is not surprising that they would have enlisted with such regiments as the Royal West Kent Regiment, the East Kent Regiment ("The Buffs") and the Royal Fusiliers (based in London) — the most 'popular' regiment after the Royal Sussex Regiment.

But many of the men commemorated at Forest Row and Hartfield had enlisted with a whole variety of other regiments across the country. Looking at south-east England as a whole, almost half (47%) the men were serving with regiments based in Sussex, Kent, Surrey, and London, but that leaves the majority serving in other regiments and corps. In fact, the 113 men in our cohort were serving in 36 different regiments and corps at the time of their deaths, including many that were not territorially based, such as the Royal Engineers, the Machine Gun Corps, the Royal Flying Corps, the Royal Field Artillery and the Royal Army Service Corps, while three were career seamen who died while serving with the Royal Navy.

One of the more unusual of these regiments was the Artists Rifles. This had been formed in 1859 in Chelsea and was popular with well-educated, cultural men. One such recruit was Private Ernest Cannon, head-teacher of a school in Forest Row. His profession exempted him from the conscription of 1916 but he later volunteered, enlisting with the Artists Rifles in October 1918. He soon succumbed to influenza, and died aged 28 at a military hospital in Essex just a week before the Armistice. Interestingly, he was the only one of the 113 men to die from influenza, despite the devastating epidemic of 1918-19.

Another consideration that needs to be recognised is that a number of men who initially enlisted with the Royal Sussex Regiment later transferred to other regiments and corps as the war progressed. Sometimes this was due to the need to backfill depleted regiments across the country. In other cases they moved to expanding non-territorial service units that applied new technologies, such as the Royal Flying Corps and Tank Corps, the latter based on an innovation that hadn't even existed at the outbreak of the war.

16. Some men commemorated at Forest Row and Hartfield lost their lives at sea

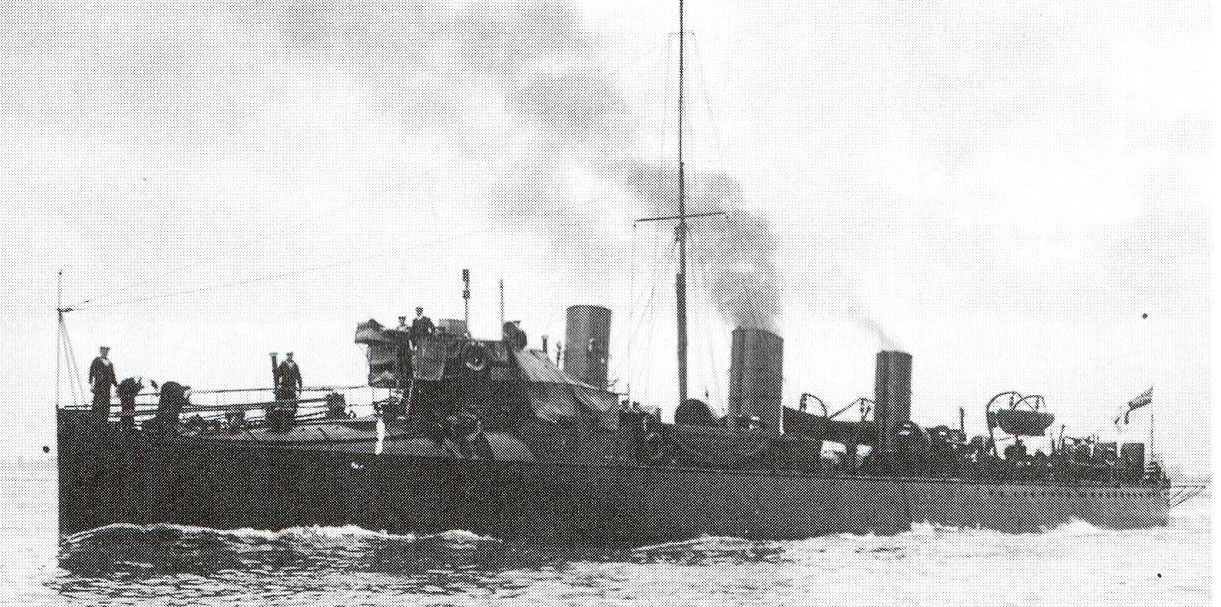

HMS Formidable and HMS Recruit, both sunk by torpedoes off the southern English coast

(Click to enlarge)

Two Ashdown men serving in the Royal Navy died when their ships were torpedoed and sunk by German submarines off the coast of southern England in 1915. Henry Biddlecombe, a ship's cook and officer's steward in the Royal Navy who died on New Year's Day 1915 when his ship, HMS Formidable, was torpedoed by a German submarine off Start Point, Devon, with the loss of 500 men. Arthur Upton, a stoker, born near Tunbridge Wells but with parents who came from Forest Row, perished when his ship, HMS Recruit, was torpedoed close to the Thames estuary in May 1915. He was one of the 39 men who were lost out of a crew of 65.

But ordinary soldiers died at sea too. Two men from our cohort — Sapper Jack Shelley, son of Hartfield's police sergeant, and Driver Ernest Vaughan, a farm labourer from Hartfield — died in the same disaster that happened during the Gallipoli campaign, when the packed troop ship HMS Hythe was rammed by another troop ship, HMS Sarnia. These ships had been shuttling back and forth with troops between Gallipoli and the Allied base at Mudros, on the Aegean island of Lemnos. The large and fast Sarnia, travelling at full speed, cut the Hythe halfway through. The Hythe sank in just ten minutes. 154 soldiers and crew were lost, many trapped inside or drowned in the ensuing chaos. Both men are commemorated at the great Helles memorial that overlooks the entrance to the Dardanelles.

17. Some men commemorated at Forest Row and Hartfield lost their lives in aircraft

The BE2c, a biplane used by the Royal Flying Corps (left). No.8 squadron arrives in France (right)

The war in the air developed rapidly between 1914 and 1918. The Royal Flying Corps, formed in 1912, and the Royal Naval Air Service, founded on 1 July 1914, expanded steadily and merged on 1 April 1918 to form the RAF. Early aircraft were primitive and unreliable, and navigation was challenging. Inevitably, there were casualties among our men — five in total. Two died in air accidents: Captain Dr. Keith Lucas FRS, aged 37, a distinguished scientist who made vital improvements to airborne navigational compasses, was killed in a collision flying over Salisbury Plain carrying out developmental work, while Captain Nigel Whitfield, aged 27, died in hospital in London after an unspecified flying accident.

Aerial observation and photography over enemy lines was a vital early role of the airmen, and three of our men were killed in action performing this important role: Lt. Frederick Polehampton, aged 41, was killed near Ypres in 1915 just a day after his squadron, which carried out strategic reconnaissance and special missions, arrived in France. Lt. Cyril Robinson, aged 22, was killed over the Somme in 1918. Lt. Eric Waters, an electrical engineer, died in 1917, aged 30, while on a photographic patrol over Flanders: his plane was shot up, and his passenger, the observer, climbed into his pilot's cockpit and succeeded in landing it near Ypres; he survived, but Eric, shot in the back and head, sadly did not.

18. Some families lost many men

In our cohort of 113 men commemorated at Forest Row and Hartfield we find that families from all backgrounds and from all levels of society, including those with more tenuous or distant links to the Forest, lost men in the war. There are ten cases where two or more brothers fell in the war, involving a total of 21 men, one fifth (19%) of the cohort. Beyond that, looking at the extended families and taking into account relations such as brothers-in-law and cousins, the ramifications of war-time losses in some cases could go much further. Below we present three examples: the Kekewich brothers, the Maskell cousins, and the Wheatley and Weeding family.

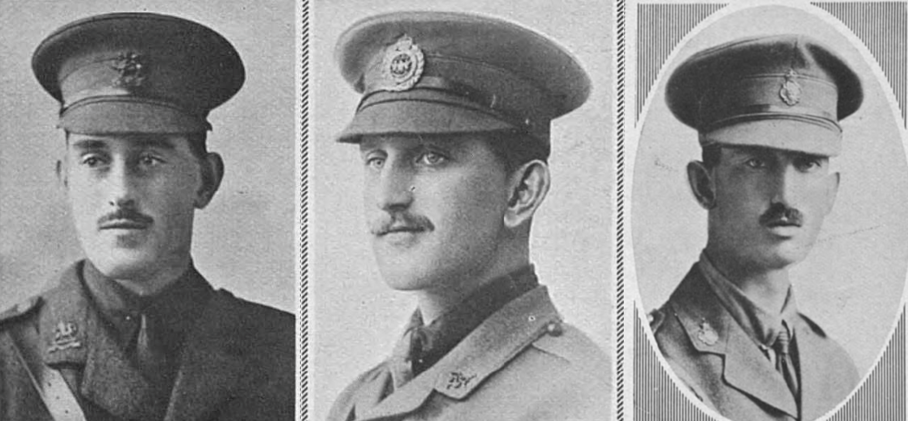

The Kekewich brothers

The three Kekewich brothers who all fell in the First World War

With respect to local families occupying the more elite levels of society, perhaps the most striking example of multiple losses is the three Kekewich brothers, John, George and Hanbury, pictured above. They were the sons of Lewis Pendarves Kekewich, a London metal trader who had acquired the grand estate of Kidbrooke Park at Forest Row before the War. They were all old Etonians who served as commissioned officers, and all three rose during the war to the rank of Captain. They served and fell in two contrasting theatres of war, George and Hanbury in Palestine and John at Loos on the Western Front. It is tempting to suggest that the brothers might not have had very strong personal links to Forest Row and to Ashdown Forest, but it is noteworthy that one of the brothers, George Kekewich, became well-known in Forest Row as the village scoutmaster before the war. For completeness, it should be noted that they had a fourth brother who served in the War and survived, later working in the War Office.

The close-knit nature of the Ashdown Forest communities meant that some families were hard hit by the losses of the war. Two families that lived in relatively humble circumstances illustrate this point.

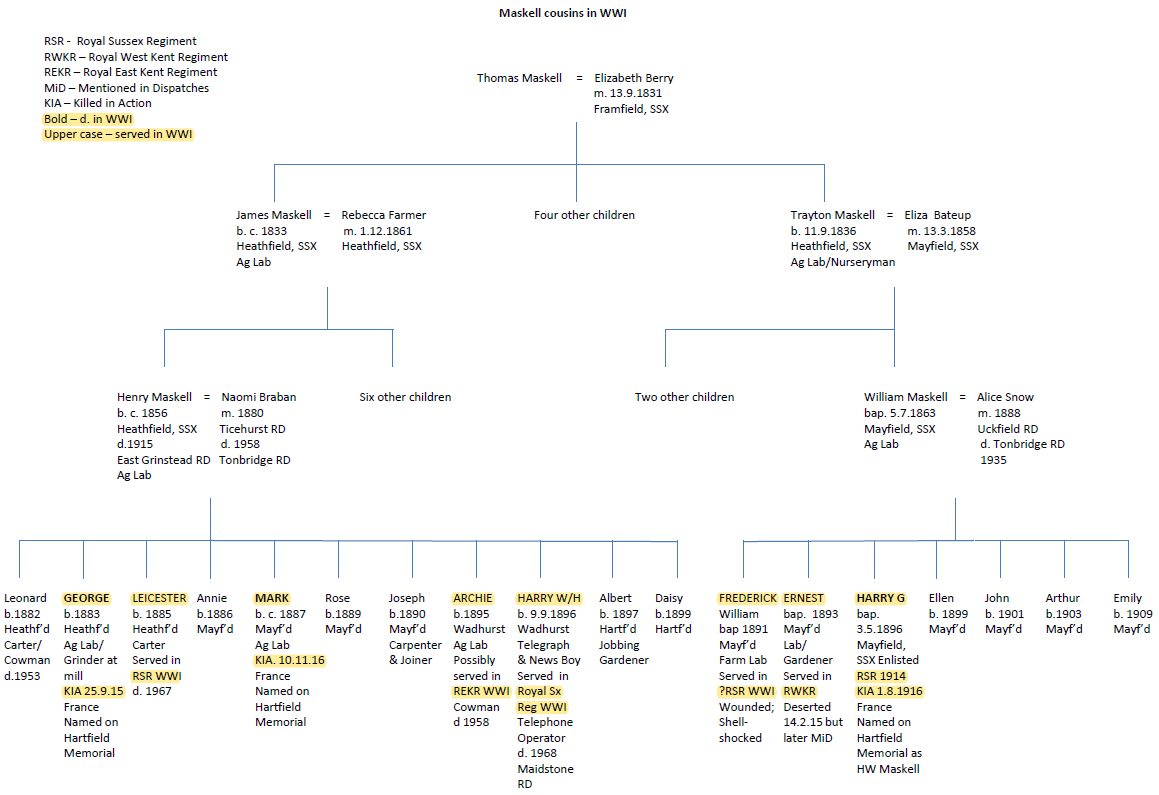

The Maskell cousins

The Maskell family tree

Two branches of the east Sussex-based Maskell family who shared a common ancestor, Thomas Maskell, lived close to each other in Hartfield just before the beginning of the war. The family tree above shows these branches, with highlighting to indicate the men who died in the War. One of Thomas' grandsons, Henry Maskell, had thirteen children including eight sons, born between 1882 and 1899, five of whom served in the war. Two, George and Mark, were killed, and three survived. Another grandson, William Maskell, had five sons, two of whom would have been too young to serve in the war. The three remaining sons did serve and of those one, Harry George Maskell, died, while another was left shell-shocked and a third deserted but was later mentioned in despatches.

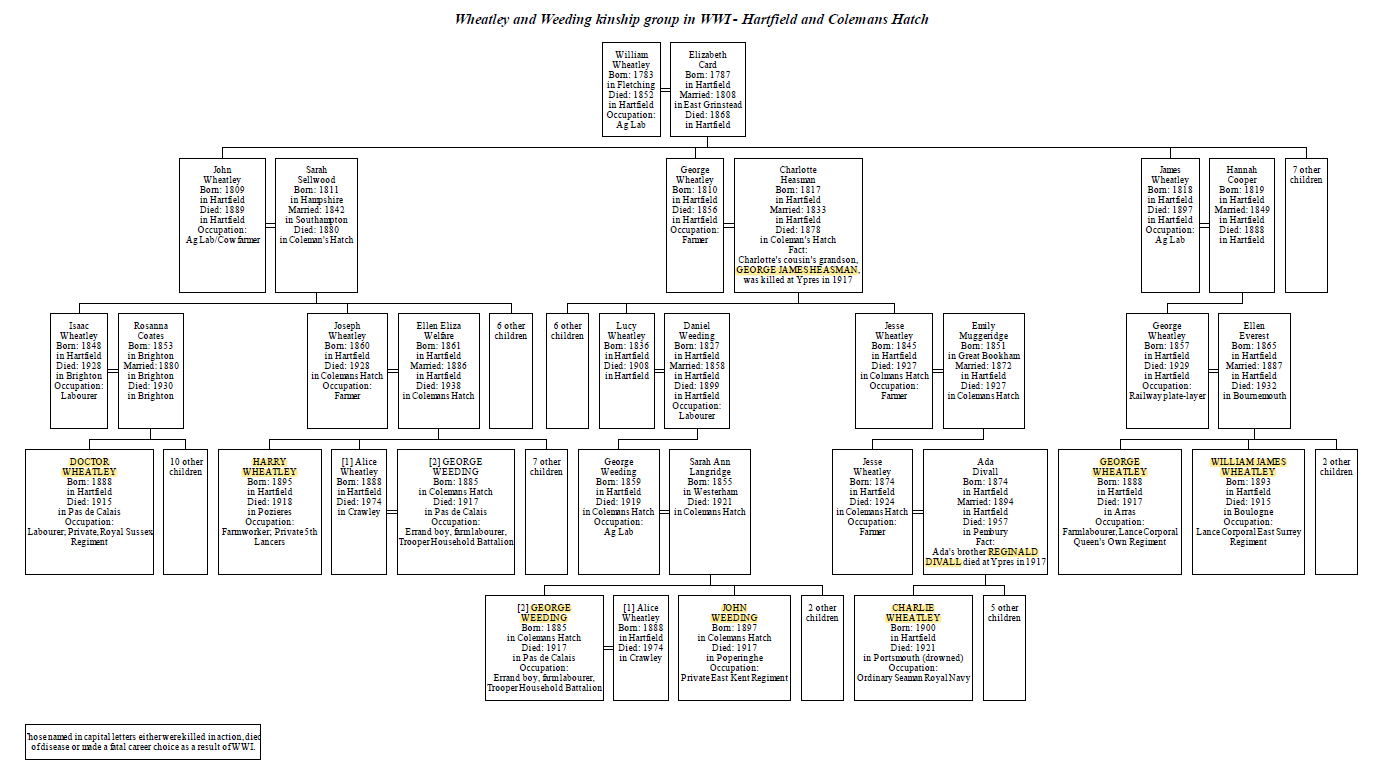

The Wheatley and Weeding family

The Wheatley and Weeding family tree

The family tree of the second family, the Weeding and Wheatley family, shown above, centred on Hartfield and Coleman's Hatch, is rather more dispersed. It shows the descendants of the William Wheatley and Elizabeth Card, who married in East Grinstead in 1808. The men who died in the War are again highlighted. It illustrates the number of deaths which this extended family suffered during the War.

Six men died who were related by common ancestry. They were cousins Private Doctor Wheatley and Private Harry Wheatley, brothers-in-law Trooper George Weeding and Private John Weeding, and two brothers, Lance Corporals George Wheatley and William James Wheatley. Another two men on the family tree were rather more distantly related through marriages, namely Privates Reginald Divall and George James Heasman. The ninth and youngest casualty of this extended family, Ordinary Seaman Charlie Wheatley, died after the war in a drowning incident at Portsmouth.

All eight of the men who died during the 1914-18 war did so while fighting on the Western Front in northern France and Belgium. It is worth making the point again that these men were fighting in places only 140 miles or so away from Hartfield as the crow flies, in countryside and among villages and towns and in weather conditions not very dissimilar to Sussex. Sussex and the Pas de Calais and Flanders were only separated from each other by the English Channel and the Strait of Dover.

And, to echo a point made elsewhere in this essay, while all eight men had been born in Hartfield, only two of them were serving with the local, county regiment, the Royal Sussex Regiment. That said, four of the other six were serving with south-eastern territorial regiments that had catchment areas that were close by. The regiments the six men were serving with when they died were the East Surrey Regiment, the East Kent Regiment (The Buffs), the Queen's Own (Royal West Kent) Regiment, the Royal Fusiliers, the 5th (Royal Irish) Lancers, and the Household Battalion.

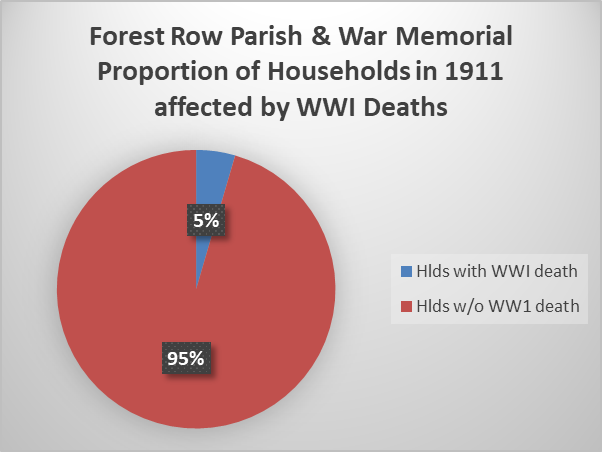

19. The relative impact of the men's deaths on the Forest Row community seems quite low

The war had a devastating impact on some families living in the parish of Forest Row, but what was the overall impact on the community?

One way of answering this question is to take the 1911 census of population of Forest Row and to link this to the men who fell in WWI and are commemorated on the Forest Row war memorial.

The 1911 census shows Forest Row to have had a population of 3,030 people, grouped into 708 households. The typical household consisted of a head, family members, servants (243), boarders (165), visitors (41), and so on. Anyone present on census night was recorded. (The census also included institutions such as boarding schools, of which there were two in Forest Row, including Ashdown House school, a small school presided over by a Mr and Mrs Evill.)

1911 census of Forest Row: households containing a man

commemorated on the war memorial as a proportion of all households

We found that 32 men listed in the 1911 census for Forest Row are commemorated on the war memorial as First World War fatalities. This compares with a total parish population of 3,030. These 32 men belong to 29 different households. A further two men named on the memorial were not actually enumerated in the census for Forest Row but were (family) members of two households who were enumerated. The combined 31 households represent one-twentieth (5%) of the 708 households identified in the census — see chart above.

Men commemorated on Forest Row war memorial as a proportion

of men enumerated in the 1911 census for Forest Row who would have been liable

for military service during the First World War simply on the basis of their age

The 1911 census data for Forest Row can be looked at in another way, in terms of the potential eligibility of the men listed there for service in WWI on the basis of their age, and how this relates to the WWI casualties commemorated on the war memorial. There was a minimum age of 18 (19 to serve overseas) and a maximum age of 38 for military service during the War. The 1911 census suggests there were 622 men in the parish who would have met these age criteria during the years 1914-18. The 62 men commemorated on the war memorial represent a tenth of this number. (Of course, some men may have been ineligible for reasons other than age, such as medical fitness, or because they were employed in exempt occupations). It may be relevant to note here that, according to War Office statistics, 7% of the men who served in the British Army during the First World War died of wounds received.*

However, the impact of the war on the local community should not only be assessed in terms of the deaths of the men commemorated on the war memorials in Forest Row and Hartfield but also of the impact of the physical and mental injuries sustained by other men from these parishes who served in the First World War but survived, injuries which they might have suffered from for the rest of their lives. War Office statistics for the First World War indicate that of all those who served in the British Army, 26% were wounded. Of those, 64% returned to full service, 18% returned to service but on restricted duties, 8% were invalided out of service.*

The impact on the local communities of the deaths of so many local men and of the return from the war into civilian life of possibly even more local men suffering from chronic physical and mental injuries is another aspect of the War that will have to be left for future research to address.

* Source: The Long Long Trail

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The Ashdown Forest Research Group's project to research the men commemorated on Forest Row, Hartfield and Coleman's Hatch war memorials who fell in the First World War began in 2013. All 113 studies were completed in time for the centenary of the Armistice on 11 November 2018.

The project, however, was not yet finished. The Group's research relied heavily on sources of information available over the Internet and during the project a huge amount of additional information became available online. The Group therefore decided to review all 113 case studies, particularly those completed early on in the project, and where necessary revised or added to them in the light of new information. This work was completed by the end of 2022. The amended studies were published on the Group's WW1 website.

The Group continues to welcome any information, photographs or images from relations or other interested parties that could be used to enhance the case studies or clarify any uncertain or incorrect information in them. Information of interest could include, for example, particulars of family relationships, the pre-war lives of the men, the details of their war service or the circumstances of their deaths. The authors may be contacted via email by clicking on the Group's email address below:

info@ashdownforestresearchgroup.uk

Ashdown Forest Research Group

19 February 2023

APPENDICES

A1. MAPS

Places of birth

Interactive map showing the men's places of birth

Click on the image above to view and explore an interactive Google map which shows the birthplaces of the men on the two war memorials. The red markers refer to men commemorated on the Forest Row war memorial (maroon to officers), the green to those commemorated on Hartfield war memorial (dark green to officers).

If a marker on the map is clicked a box will be displayed indicating the man's name, the war memorial on which he is commemorated, his place of birth, with a hyperlink to the Group's case study.

Clicking on the top left of the map reveals a list of all the men on Forest Row and Hartfield war memorials.

Cemeteries and Memorials

Interactive map showing cemeteries where the men are buried

and the memorials where they are commemorated

Click on the image to view and explore an interactive Google map which shows the cemeteries where the men on the two war memorials are buried (blue markers) or, if there is no known grave, the memorials where they are commemorated (red markers).

A2. TABLE

Summary table listing the cemeteries and memorials where the men are buried or commemorated. (Click on image to view).

A3. LINK TO THE CASE STUDIES

The case studies may be viewed online at the Group's World War One website (opens in new window).

A4. SOURCES AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Click HERE for a page listing sources and acknowledgements.

A5. FURTHER READING

The books below by Grieves (2004) and Tiller (2013) are particularly recommended as background reading.

Berry, M. (2017) 'Researching the Men of Ashdown Forest who fell in the First World War', Ashdown Forest News. (PDF download)

Berry, M. (2018) 'Officers and Ranks who Fell in the Great War — The Kekewich and the Maskell Brothers', Ashdown Forest News. (PDF download)

Grieves, Keith (1999) 'Sussex in the First World War', chapter 58 in Leslie, K. and Short, B. An Historical Atlas of Sussex. Chichester: Phillimore & Co Ltd.

Grieves, Keith (2004) Sussex in the First World War. Lewes: Sussex Record Society. 394pp. ISBN-13: 978-0854450565.

Griffiths, P. (2014) 'Forest Row Men who died in the Great War', Ashdown Forest News. (PDF download)

Griffiths, P. (2019) 'Men of Ashdown Forest who fell in the Great War: A Case of Mistaken Identity', Ashdown Forest News. (PDF download)

Tiller, K. (2013) Remembrance and Community: War Memorials and Local History. Ashbourne, Derbyshire: British Association for Local History. 56pp. ISBN-13: 978-0948140013.

Smith, Victor (2004) 'Kent and the First World War', chapter 66 in Lawson, Terence and Killingray, David, An Historical Atlas of Kent. Chichester: Phillimore & Co Ltd.

The War Office (1922) Statistics of the War Effort of the British Empire during the Great War, 1914-1920. London: HMSO.