ERIC GORDON WATERS

Lieutenant, Hants Carabiniers and 6th Squadron, Royal Flying Corps

Killed in Action flying over Poperinge, West Flanders, Belgium,

on 24 January 1917, aged 30

Buried at Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery, Poperinghe

Grave Reference: Plot X, Row A, Grave 1

Eric Gordon Waters

Eric Gordon Waters was born in Forest Row in 1886, son of James and Elizabeth Ann Waters. James had married second wife Elizabeth Ann Woodhead in Kensington in 1871, and Eric was the ninth of their 12 children. The census returns show Eric living at Oakcroft, in Forest Row, a house situated where the present Christian Community Church now stands in Hartfield Road. James Waters was a builder and some of his brothers followed their father into the construction business, either as builders or carpenters; the family firm is still operating today. Eric, however, chose to follow a career as an electrical engineer, which is how he is recorded on the 1911 census, and he appears in a list of students in the Journal of the Institution of Electrical Engineers in 1903 (click here to view). Before the war he worked for Messrs Ferranti Ltd, and was the inventor of both the Callender-Waters and Ferranti-Waters cable protection systems.

A reference in the National Archives catalogue suggests that 2nd Lieutenant Eric Gordon Waters was connected to the Royal Garrison Artillery in 1914, although the London Gazette posted him as 2nd Lieutenant in the Hants Carabiniers as of 19 October 1914. It also notes that 'Second Lieutenant Eric Gordon Waters is appointed to command the 1st South Western Mounted Brigade, Signal Troop, and is seconded while so employed'. However, he was also still operating as an electrical engineer as on 31 August 1915 he was granted a patent on an electric protective system (which he filed in April that year) which related to the protection of electric systems formed in sections, for example, ring main systems (click here to see the patent record).

He was appointed Assistant Instructor at the School of Military Engineering, Brightlingsea, Essex, on 12 September 1915. While stationed there he was summoned for 'driving a motor car in a manner dangerous to the public' at Chelmsford on 9 October. He apparently took a corner so fast that his vehicle ended up on the wrong side of the road, narrowly missing a cyclist, and skidding 10 feet when the brakes were applied. Waters denied the charge, but was fined 50 shillings and 10 shillings costs anyway (source: British Newspaper Archive).

He retained the Instructor post until 5 June the following year, when he was attached to the Royal Flying Corps, No.6 Squadron. In September 1916 he gained his certificate, and was sent to France on 2 October. He was apparently wounded escorting a photographic patrol. His plane was shot up; the observer, Sergeant Slingsby, climbed into the pilot's cockpit and succeeded in landing between Vlamertinge and Ypres. He survived, but Eric, shot in the back and head, did not. He was 30 years old (click here for his Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery details).

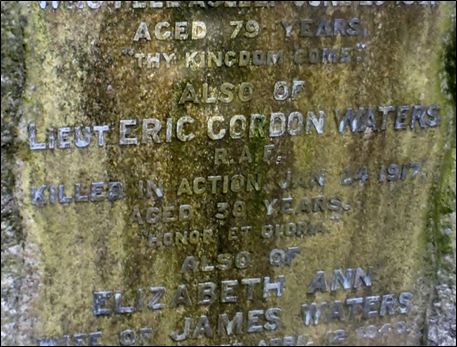

Lt. Eric Waters' gravestones in Forest Row cemetery (left) and

Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery (right)

A letter dated 26 January 1917 from Major Barrett of the R.F.C. states that Waters was buried that day at 2 p.m. at No. 10 Casualty Clearing Station. Another condolence letter, from Major T.A.C. Wright says:

It is difficult to say how we all miss poor old Eric. He was a splendid fellow and was the prime mover in all our amusements in the mess.

Probate of his estate was granted to his mother Elizabeth Ann Waters, with effects valued at £1,215 17s. 3d.

Monogram from the memorial book

for Eric Gordon Waters

After his death, his parents created a tribute to their son, consisting of letters of condolence, a photograph and a letter from Eric himself. As well as a telegram from Buckingham Palace, there were letters from fellow officers in the RFC and at Brightlingsea, from some who were trained by him, and people who had worked with him at Ferranti. Major Barrett, of the RFC, explained that Eric had been escorting another 'machine' of the squadron, which was taking photos when they were attacked by two other hostile planes:

He engaged one of them and during the encounter the Hun dived on him and he was hit in the body and must have died almost at once.

The officer under escort saw Eric's machine falter and initially fall out of control before the observer was able to right it.

There are numerous moving tributes, but perhaps the most touching letter of all is the one written by Eric himself to his parents in December 1916. It begins:

Today is a beautiful day — rain, thunder and mist — beautiful, that is, from the aviator's point of view, for though flying is possible, no use can be made of it...

Yesterday I was detailed for a bombing raid, which proved to be the most enjoyable one I've had up to now. Clouds were massing when we left the ground...We always fly in close formation, which, though it calls for a great deal of care, usually "puts the wind up", otherwise frightens hostile machines away. We then proceed on the fateful journey — fateful for someone, for the bombs we carry weigh a hundredweight each — two to a machine.

He goes on to describe the protective effect of the clouds, the puffs of 'Archie' or flak, the loss of aircraft during the raid, the fear of attack from 'the Hun', who on this occasion did not appear, and the 'grand sight' of 'spotless white' clouds as he flew above them in the sunshine. The letter ends with a P.S., which seems prophetic in hindsight:

Charlie Watson's death was not "awful". It was simply splendid. To die for a good object and in full possession of all one's faculties is to have died well — infinitely preferable to dying simply of old age.

Pam Griffiths

14 December 2014

Updated 7 July 2019

Acknowledgement

Memorial Book image kindly shared by Mollie Smith, Nutley Historical Society.