EWBERT JOHN SHELLEY

Sapper, 2209, 1st/3rd Kent Field Company, Royal Engineers

Died at Sea, 28 October 1915, aged 20

Commemorated at the Helles Memorial, Gallipoli, Panel 24 to 26 or 325 to 328.

Ewbert John Shelley

Click to enlarge

Sapper Ewbert John ("Jack") Shelley is one of two men commemorated on Hartfield war memorial who in 1915 were lost at sea in the sinking of HMS Hythe during the Gallipoli campaign (25 April 1915 - 9 January 1916). This was the unsuccessful attempt by Allied forces to seize the Gallipoli peninsula, on the northern bank of the Dardanelles, a vital part of a plan to capture Constantinople, the capital of the Ottoman Empire. The other man, Driver Ernest Stanley Vaughan, is also profiled here.

Jack Shelley was born in Frant, Sussex, in 1895, the son of William (b.1866) and Alice Shelley (b.1864), later of Holly Croft, Hartfield, Sussex. At the time of the 1901 census he was living at Haddon Cottages, Bexhill, Sussex. In the 1911 census Jack was enumerated as living at the police station in Hartfield, with his occupation given as house boy. His father, William Shelley, was the police sergeant for Hartfield, and died in 1958 aged 90. His mother, Alice died in 1937.

Jack's father, William Shelley, in his police uniform. Date unknown.

Click to enlarge

Jack had two siblings, and elder brother, William Arthur, born a year earlier, and Frederick Harold, born a year later. At the time of the 1911 census William was an assistant grocer and Frederick was a grocer's errand boy. In the 1939 register William is listed as a coal and coke merchant, married to Edith, with a daughter at school. William died in 1954 aged 61, while Edith died in 1978 aged 78. Frederick died in 1962. He lived at The Chestnuts, Hartfield. In 1939 he was a haulage contractor for livestock, married to May, with a son, John, at school.

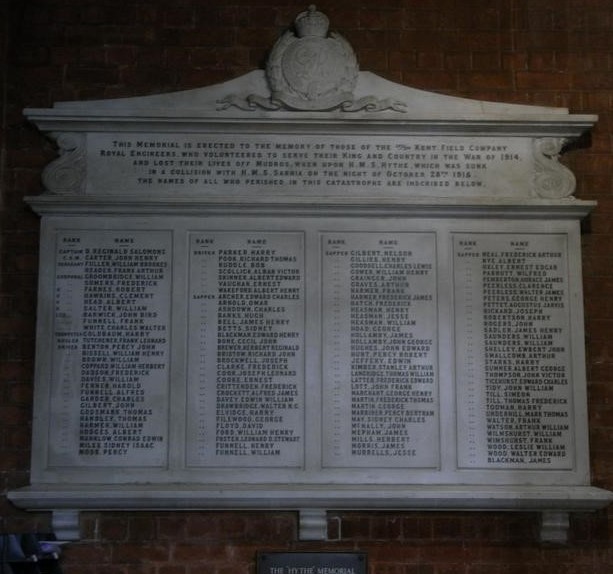

The "Hythe" Memorial at St Matthew's Church, High Brooms.

It was previously at the Drill Hall in Southborough until 1965.

(Click to enlarge)

The Kent & Sussex Courier on 12 November 1915 reported:

"The sad news of the drowning of Sapper John Shelley and Sapper Ernest Vaughan of the 3rd Kent Engineers was received in Hartfield on Saturday morning and the deepest sympathy was expressed on all sides as both the young men were well known and esteemed and came from highly respected families.

It only seems a few weeks ago that they passed through the village with their ill-fated comrades on their way from East Grinstead to Tunbridge Wells and were looking forward with much keenness to going on active service.

John Shelley was the second son of ex-Sergeant W Shelley, and Ernest Vaughan one of the youngest sons of Mr Thomas Vaughan. Both were educated at the village school and were regular members of the Church, John being an old choir boy.

On leaving school they became very keen students of the Night School and also members of the Gymnastics Class, and were very popular, good-natured lads.

They joined the Regiment a few months ago. Both have brothers serving in the Army, William and Fred Shelley and Albert John and Walter Vaughan respectively.

On Tuesday morning at 8, a Requiem Communion Service was held when, in addition to the members of the bereaved families, there were present Mrs Hogg, Miss Paul, Mr AB Medhurst, Mr J Medhurst, Miss K Medhurst, Mr E R Stringer (their old schoolmaster), and others, the Rev W A Bickles officiating."

The Sinking of HMS Hythe

On 11 October 1915, 231 men of the 1st/3rd Kent Field Company of the Royal Engineers sailed out of Devonport, Devon, bound for the eastern Mediterranean and Gallipoli — just too late for the War Cabinet's decision of the previous day to stop sending any more troops to Gallipoli.

The Helles Memorial, Gallipoli, Turkey

The voyage out to the eastern Mediterranean was uneventful. At Mudros Bay, on the Greek island of Lemnos in the northern Aegean sea, most of the Company transferred to a smaller ship, the HMS Hythe, a cross-channel paddle-driven ferry built in 1905 and requisitioned from the South East and Chatham Railway to be initially used as a minesweeper, to transport them to Helles, on the Gallipoli peninsula.

The Company was formed from Territorials, so few of them were regular soldiers. On 28 October 1915, the troopship HMS Hythe was sunk approaching the Dardanelles. HMS Sarnia, another troopship steaming away from shore after disembarking her troops, collided with the Hythe, which went down in ten minutes. The Hythe was sailing without lights in order to avoid detection by Turkish batteries on the shore. The Army Officers were allowed to enter the engine for warmth for most of the journey, and the men crowded the decks, the drivers to the fore well deck and the sappers to aft during the passage. Accounts speak of being very crowded, almost shoulder to shoulder. Because of the weather and the choppy seas, an awning was erected from side to side of the Hythe to provide some overhead cover against rain and spray, and many of the soldiers huddled underneath.

There were 275 men on board including crew, and 154 of them drowned. 129 of these were men of the 1st/3rd Kent Field Company, Royal Engineers, from Tunbridge Wells, Southborough, and the surrounding region. Twenty-four of them are named on Southborough War Memorial.

Major Ruston described what happened on 28 October 1915:

"We had sailed from Mudros about 4pm. It was a rough and squally day and...a great number of the men were seasick. However, we had almost reached our destination [about 8pm] and were beginning to think about disembarking when suddenly a large vessel loomed out of the darkness and in spite of all efforts to avoid a collision it ran into us, cutting deep into our port bow and bringing down the foremast. In ten minutes the vessel sank, leaving numbers struggling in the water or hanging on to spars and other floating matter. The boats of the other vessel did all they could and picked up many poor fellows - but all too few, for nearly 130 men drowned."

The vessel that ran into the overcrowded Hythe was another British troop ship, the Sarnia, which was returning to Mudros Bay having left her passengers at Helles.

Some of the men were killed by the actual collision, some were trapped in the sinking ship, and others were drowned in the chaos that followed and in the scramble for the few life-jackets that could be grabbed before the Hythe went down. In total 154 soldiers and crew died that night.

HMS Sarnia was also a requisitioned ferry, built in 1910 for the London and South Western Railway. In war service she became an armed boarding steamer. With a displacement of 1,498 tons and a top speed of 20.5 knots, Sarnia was a much larger and more powerful vessel than the Hythe, whose limit was only 12 knots.

Both vessels had made at least one change of course but it seems that neither slowed down. The Sarnia struck the port side of the Hythe with such force that its bows cut halfway through the ship. That brought the Hythe to a dead stop and caused its mast to collapse on the awning. Numerous deaths were caused instantly by the bows and the mast but those remaining fared little better. The immense damage caused the Hythe to sink rapidly. It was all over in a little as ten minutes. Many drowned trapped under the awning or in the cabs of their vehicles. The others had little or no time to gain the railings and throw off their kit before they were in the sea. Panic reigned as soldiers scrambled for the few life-jackets that could be grabbed before the Hythe went down. Most of those who jumped overboard were drowned in the chaos that followed.

Although HMS Sarnia survived the collision with the Hythe, it was later sunk by torpedo in the Mediterranean on 12 September 1918.

Carol O'Driscoll

29 April 2014

Last updated 7 December 2023 (with thanks to Richard Coomber of the Hartfield History Group for additional information).

Source:

Judith Johnson: The Sinking of HMS Hythe - 28 October 1915 (Blog, 26-10-2012)