HAROLD GRAYER

Private, M/339580, Royal Army Service Corps,

648th Mechanical Transport Company.

Died of pneumonia in hospital in Pemba, Cabo Delgado,

Portuguese Mozambique, 9 December 1918. He was aged 28.

He is buried in Pemba Cemetery, Mozambique,

in the former Portuguese East Africa.

Pemba Cemetery

(Click to enlarge)

Harold Grayer was the son of Josiah and Sarah Grayer and husband of Florence Grayer of 2, Morris's Cottages, High Street, Forest Row, Sussex. He was born in Hove, Sussex, in 1890 and had eight siblings at the time of the 1901 census. His father was listed as a coachman. His elder brothers, Reginald and Albert, were listed as grooms. Albert also served with the Royal Army Service Corps (RASC), enlisting in December 1915 aged 27. He survived the war and died in Brighton in 1967. There is no record of his brother Reginald serving in the war.

In the 1911 census Harold was listed as a domestic motor cleaner, aged 20, living at Staplefield Place, Staplefield, Sussex (about 15 miles south-west of Forest Row).

Staplefield Place, Sussex

(Click to enlarge)

Harold married Florence Emily Lily Grisbrook in the autumn of 1915. Florence was born in Forest Row on 16 August 1891. Her father was listed as a coal car man in the village in the 1901 census and as a bricklayer in 1911. He died, aged 50, in December 1918. In 1939 Florence was living in Brighton, listed as a widow and an unpaid domestic servant. She died, aged 91, in 1982.

Harold and Florence had a child, Wilfred Llewelyn Grayer, born 8 May 1917. He lived until 1994 and was a postman in Brighton from 1936. In 1939 he was listed as a sorting and telegraphic clerk, living with his mother and maternal grandmother in Harman Villas, Brighton.

Florence's brother Alfred Llewellyn Grisbrook enlisted on 8 April 1916, joining the 13th Service Battalion of the Royal Sussex Regiment and serving with the British Expeditionary Force in France and Flanders. Alfred was killed in action on 21 December 1916. He is covered in another case study compiled by the Ashdown Forest Research Group.

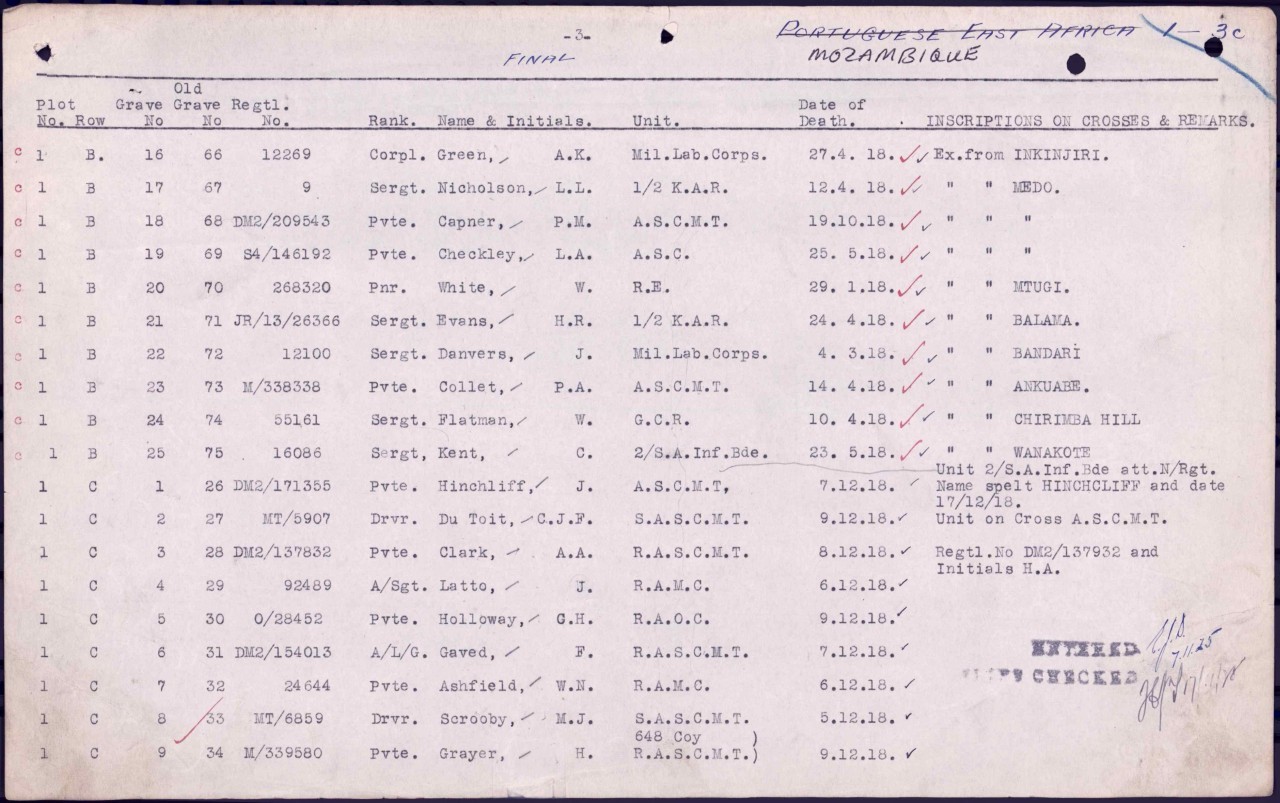

Pemba Cemetery listing showing Harold Grayer's

entry on the bottom line

(Click to enlarge)

Harold Grayer died in Portuguese Mozambique serving with the Royal Army Service Corps 648th Mechanical Transport (MT) Company.

The Royal Army Service Corps was the unit responsible for keeping the British Army supplied with all provisions apart from weaponry and ammunition, which was the responsibility of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps.

The Royal Army Service Corps in action

(Click to enlarge)

The RASC 648th Company was formed on 9 February 1916. Originally a water tank company [MT] in the UK, it then went to East Africa. The company's role in East Africa was as the 4th Auxiliary [MT] Company [maintenance services] Artillery Support. The campaign in East Africa can be symbolised by the contrast between the machine gun, one of the most modern weapons, and the fact that this technology was carried by African porters. The lack of sufficient railways in East Africa, or roads that could be used by motor cars, meant that the moving armies relied on the most basic form of transport: human carriers. An established system of African porter transport existed in the region prior to the war. But the enormous demand for carriers by all armies resulted in an unprecedented number of ordinary people — men, women and even children — being persuaded or forced into porter services.

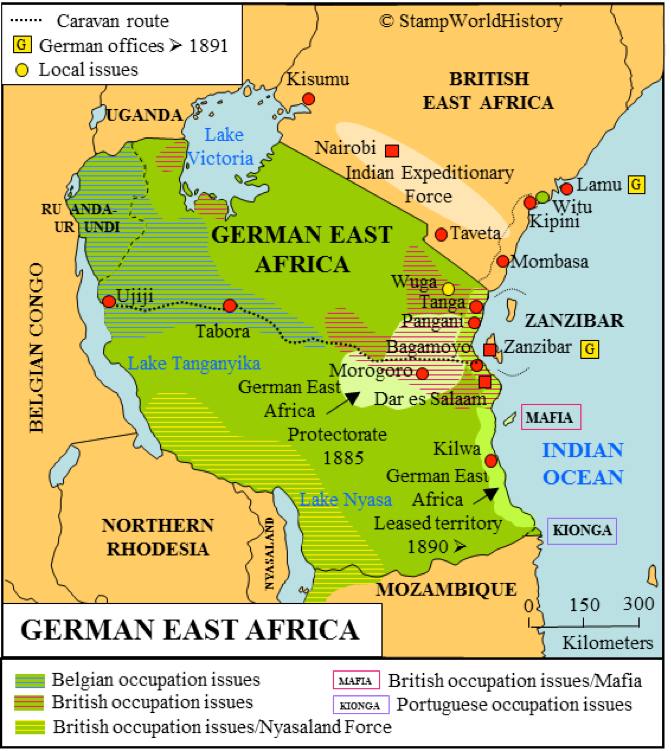

The British brought in troops from the United Kingdom, India, South Africa, Nigeria, the Gold Coast, the Gambia, the West Indies, Nyasaland as well as both North and South Rhodesia to fight alongside with those from the Belgian Congo and Portuguese Mozambique. The opposing Germans, cut off by sea and blockage, used ingenuity, endurance and ruthless exploitation of their colonial subjects to survive in the field until the final Armistice in November 1918.

Royal Army Service Corps poster

(Click to enlarge)

In contrast to the Western Front, the distances in East Africa were enormous and troop levels were low. Although there were a number of pitched battles, operations in East Africa were dominated by that of patrols and isolated columns moving through heavy bush with the nerve-wracking and constant threat of ambush. It was not uncommon for columns to advance a hundred miles through dense bush with their bases far in the rear and dependent on civilian carriers to move their supplies on their heads. Most of this had to be accomplished while marching on foot in terrain that ranged from arid deserts to tropical jungles to formidable mountains and usually on inadequate rations and in ragged clothing. Apart from the enemy, soldiers had to contend with dangerous wild animals such as lions, elephants and hippos as well as the clouds of voracious insects that carried pestilence and made life a misery. The results were unprecedented levels of sickness, including malaria, dysentery, and pneumonia, for humans, while nearly every single pack animal perished from disease.

It was to be a greatly expanded African force that led the clearance of German East Africa in 1917 and then the pursuit through Mozambique in 1918. They were backed by the thousands of carriers who moved their food, equipment and ammunition as well as the hundreds of thousands of others who worked for the war economy.

East Africa before the First World War

(Click to enlarge)

Harold left £25 & 18 shillings in his will. This was shared between his widow Florence and his son Wilfred.

Harold Grayer is listed on the Forest Row war memorial.

Carol O'Driscoll

5 September 2018

Last updated 28 October 2021

Sources:

Ross Anderson 'The Forgotten Front: East Africa 1914-1918' (The History Press)

Daniel Steinbach 'Misremembered history: the First World War in East Africa' (British Council, 9 April 2015)

Map: Ana Paula Pires

'The First World War in Portuguese East Africa: Civilian and Military Encounters in the Indian Ocean' (e-journal of Portuguese History, Vol.15, Number 1, June 2017)